Feature

A New Home in Christ

As the debate about asylum seekers rages in Europe, Persian migrants are finding forgiveness in Jesus Christ and an eternal home in His Body, the church.

Water gushed from a flagon, splashed over Sebastian’s head and sloshed into the silver bowl, spattering the wooden baptismal font and floor, as the pastor said, “Ich taufe dich im Namen des Vaters und des Sohnes und des Heiligen Geistes. Amen.” (“I baptize you in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.”) Moments before, in his native tongue of Farsi, Sebastian renounced the devil and all his works and all his ways. He also renounced “Islam, Muhammad and the 12 imams, including Jamal Ali.”

“Lutheran theology is the perfect opposite of Islam,” said the Rev. Dr. Gottfried Martens, pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church, Berlin-Steglitz, Germany. The god of Islam is very far away and very large. But “now [the Persian migrants] experience, especially in Lutheran theology, that God is making Himself small, so small that you can even touch Him with your lips in the Sacrament.”

The Shia branch of Islam, from which Sebastian and many of the men at Trinity converted, lacks any assurance of salvation. Shiite theology believes everyone will go to hell, and Allah will rescue some people from it. “They could never be certain of salvation,” Martens said, which is why they love Lutheran worship. To bring this comfort home, Martens personally absolves every member in the Divine Service at the Communion rail, laying on hands and declaring: “Your sins are forgiven you.”

Complicated Migration

Trinity Lutheran Church is a unique German congregation. Of its 1,600 members, 80% have migrated from Persian countries such as Iran and Afghanistan and worship in Farsi. Some of its members travel up to five hours to attend worship. Around 30 attendees live in temporary “church asylum” in Trinity’s basement.

This outreach to Farsi speakers began in the early 2010s in Leipzig and soon expanded to Berlin and Hamburg. In 2015, Middle Eastern conflicts drove record numbers of refugees and asylum seekers to the European Union (EU). As immigration increased, migrant-related crime also increased. Along with an increased burden on social services, this began to change attitudes in the EU toward asylum seekers.

Sweden, for example, recently voted to pay the equivalent of $34,000 USD to migrants who return to their home countries. It has also placed limits on migration and is deporting current asylum seekers to such a degree that it expects to experience net emigration in 2024 (that is, more people leaving Sweden than entering), the lowest immigration into Sweden since 1997.

These deportations, however, come with significant costs for the migrants. Many have lived in Sweden for a decade or more. “In Sweden,” said Isa, one of Trinity’s asylum seekers, “I studied high school. I studied in university. I worked. But Sweden says, ‘You cannot stay.’” The Swedish government wants to send Isa back to Afghanistan, his parents’ country of origin, but a land in which he has never lived.

The cost for him could, potentially, be his life.

Daniel, whose parents are also Afghan, lived in Iran until he was 15. He fled to Sweden, where he finished high school, attended university and found a job. The Swedish government wants to deport him back to Afghanistan. Like the vast majority of Trinity’s Afghan asylum seekers, Daniel is ethnically Hazara, a minority Shiite people group in Afghanistan. “The Taliban openly say they want to kill all Hazara,” said Martens. The Taliban, a Sunni group, consider all Shiite Muslims to be infidels.

But Isa and Daniel and many others at Trinity have since become Christians. According to Islamic law in Afghanistan, such apostasy from Islam is punishable by death for men and life imprisonment for women. For those being deported to Iran, the situation is the same. Open Doors’ World Watch List, which tracks violence against Christians, puts Iran in the No. 9 slot of countries with the most extreme persecution.

Faced with the threat of deportation to face death or prison, many Iranians and Afghans flee to Germany. EU regulations prevent them from immediately applying for asylum in a second EU country; therefore, they hide in Germany for six months to escape deportation to Sweden and thus Afghanistan.

Church Asylum

Here’s where Trinity steps in. It provides church asylum for these Christian men, most of whom become Lutheran. For the time being, the German government allows church asylum. Martens reports that he has “sent a lot of papers about every person to the state.” Sandra Preuett, a member of Trinity, explained: “The church asylum program takes these people in, and out of respect for the church body, the police will not enter the building to remove those people [to] return them to the country they came from.”

At Trinity, the men find a home and a community in which to live and learn about Lutheranism while they wait to claim asylum in Germany. They eat together, worship together, learn German together. “Somebody described it like a monastery,” Daniel said.

Barad, the “chief” of the community, organizes the daily life of the men. Despite his heavy duties, he said, “You don’t have any stress here. … You feel calm here because you think that you live with a big family.”

Recent actions of the German government seem to indicate that less tolerance for church asylum may be on the horizon. This spring, police in Bienenbüttel raided a parish hall to arrest and deport a Russian family. Other regions seem to be signaling similar movements. Martens also noted an increase in rejected asylum applications: “The German authorities always think that when somebody says he’s a Christian, then he’s a liar.”

Nevertheless, Trinity continues to preach God’s Word and administer the Sacraments for the good of the Christian souls entrusted to this congregation.

Dreams of Jesus

“As Lutherans, we are very sober, and normally we don’t like to hear about dreams and things like that,” Martens said. Imagine his surprise when asylum seekers started to share their dreams with him. He eventually learned that “dreams have a totally different meaning in the culture of Iran.”

Sebastian has dreamed of Jesus since he was 7 years old, despite having no knowledge of Christianity. He hesitates to talk about his dream. “I’m a medical doctor; I have [a lot] of experience with patients. Dreams is a borderline thing because pathological dreams can mean schizophrenia,” he said. “So, you can’t talk about dreams with just anyone.”

Nevertheless, he was willing to share his dream: “I am a little kid around 2 years old. … [I’m sitting on] a white stone. … And a great big man with a cross on his neck comes and picks me up, and I start laughing.” For over 30 years, the dream remained the same. Only after he visited Trinity did the dream change. After that, he no longer sat on a huge white stone, but inside the sanctuary of Trinity Lutheran Church in Steglitz.

Martens now regularly teaches catechumens about dreams: “You always have to check the dreams according to Holy Scripture. Once somebody sees Jesus and Jesus says, ‘Go to church and get baptized,’ then I agree, that’s the real Jesus.” The dream must point to the Word and Sacraments.

No Strategy But the Word

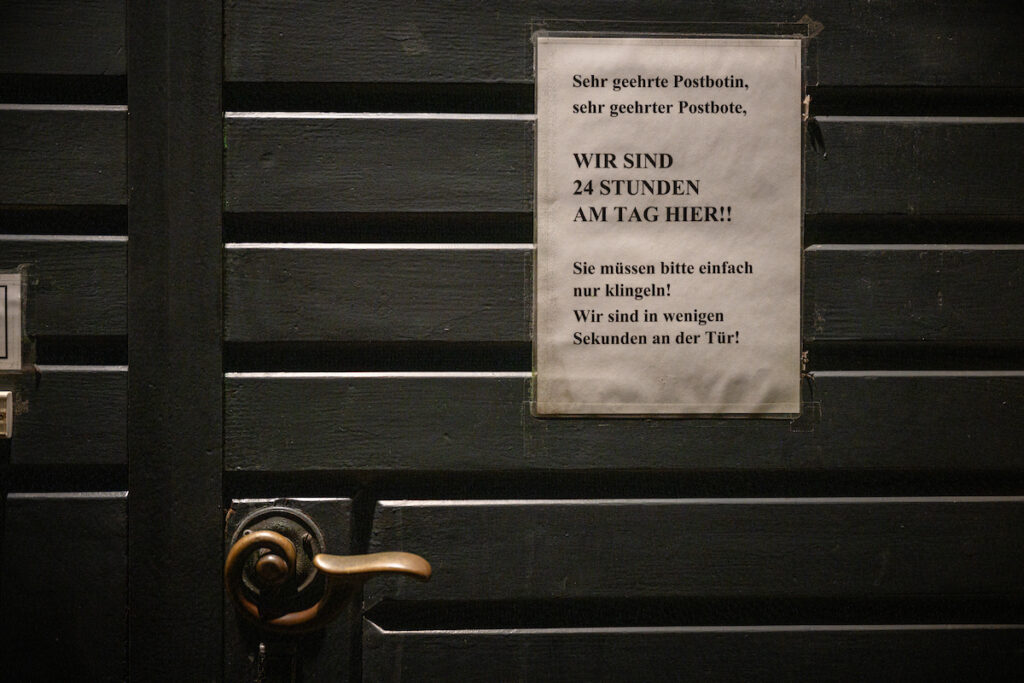

“In the States, we used to have to more or less jump through hoops to get people into the [church] doors,” said LCMS missionary Rev. Dr. Christian Tiews. “Here it’s the opposite. Here they literally almost beat down the doors.”

The work in Germany, especially Berlin, is exploding. When asked about his strategy, Martens gave a sly grin: “We don’t have any strategy. We don’t have any method. I always say our method is just Word and Sacrament and nothing else. When these people hear the Gospel, they can’t be silent. They invite their friends.”

And so it is. The church gathers for the Divine Service: in Farsi on Friday night, Saturday morning and Saturday evening; a German service on Sunday morning; and another Farsi service Sunday afternoon. At the heart of the congregation’s work is the desire to preach and proclaim God’s Word, to baptize with water and the Word, and to feed God’s people with Christ’s body and blood.

These Persian Lutheran Christians, some traveling for hours, will spend the night in the church, sleeping on the floor of the fellowship hall or in the church balcony to attend services the next day. The Germans and Persians also eat together between services on Sunday morning.

Now, LCMS missionaries are looking to expand to other enclaves of Farsi speakers. This may include London, Paris and one “little village in Southern California they call Tehrangeles,” Tiews said. “There are no less than 700,000 Persians in Los Angeles, the second largest [population of Iranians] outside of Tehran.” They call this ministry simply “The Persian Project.”

It’s an uphill battle. The Rev. Dr. David Preus, LCMS Eurasia regional director, noted that the conversation about immigration is often deeply tied to politics. But Preus also pointed out: “You have more in common with … these Iranians, Afghans, … than you have with many of the people you live with in your hometown because you confess the same Christ.” He trusts God’s Word to do its work: “They’re hearing this [Gospel] message. They’re believing it. They’re confessing it. They’re going to the Lord’s Supper and receiving forgiveness.”

And that’s our hope: that men and women like Sebastian and Daniel and countless others, who have been cast off from one country to another throughout their lives, would find an eternal home in Christ, among His Body, the church.

Learn More

- Learn more about mission work in Eurasia

- Listen to a podcast on this topic from The Lutheran Witness

- Make a gift to support LCMS International Mission

Share Jesus with the World

Your generosity today makes possible your Synod’s witness and mercy efforts both at home and abroad.

Are you looking to direct your gifts for work that’s more specific?

Visit the LCMS online ministry and mission catalog to find those opportunities most meaningful to you!

Don’t see what you’re looking for?

Contact LCMS Mission Advancement at 888-930-4438 or mission.advancement@lcms.org to talk about all the options available.

Rev. Roy S. Askins

Managing director of Editorial and Theological Content for LCMS Communications and executive editor of The Lutheran Witness.